It’s not news that multifamily construction is bottlenecked. We’ve already documented in this space how construction delays are one of the issues exacerbating the current housing shortage. Builders would have to crank out 30,000 more units per year, we reported, just to keep up with demand. But the problem is likely to get worse before it gets better.

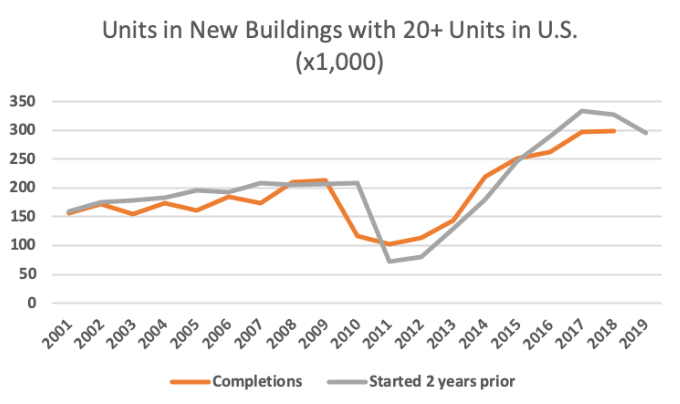

For this article, we took a look at some U.S. Census Bureau data about housing starts. Peeling away the small-scale projects that contribute to the headline numbers, we focused strictly on projects that are expected to add 20 or more apartments each to the landscape. Then, going with the rule of thumb that these projects typically take two years to complete, we compared how many units ought to have been completed in a given year with how many were delivered. It’s not pretty.

The first odd thing about this graph is how steady and in-tandem starts and completions were in the early years of the Millennium — right up until the real estate market fell off a cliff. As the U.S. emerged from the Great Recession, completions exceeded starts, presumably because so many projects were put on hiatus as demand and capital dried up. But 20-plus-unit starts soon made up for lost time, and the number of big-project apartments completed in 2015 matched those promised in 2013 almost exactly, in the neighborhood of 250,000. Still, that was 50,000 more than in any year in recent history, and it soon became clear that the industry was reaching capacity. Last time that many units came online at once, The Godfather was still in theaters. This past year we reached the point where developers are getting shy about breaking ground on new projects until the current ones are farther along the pipe.

Things were bound to fray. The multifamily homebuilding industry has hit its ceiling, absent some massive public policy initiatives such as the Housing Act of 1949. (This paeon to government overreach and unintended consequences might have destroyed more homes than it built, but that’s another story.)

According to RentCafe, multifamily unit completion volumes are expected to be 8.2% lower in 2019 than they were in 2018, which were 8.2% lower than the year before. That supply trend is, of course, moving in the opposite direction of the demand trend.

“High construction costs and a narrow pool of skilled labor are just a few of the factors hindering the development of new apartment units,” blogs Florentina Sarac.

Must investors adjust their thinking to assume that a typical project is going to experience another six months or so of burn rate before the ribbon gets cut and that the cash stream won’t start flowing back until that half year is up? Do they have to face a new reality that the rate of return on a multifamily project will henceforth be lower than it has historically been?

Contributing Factors to Construction Delays

The short answer is “yes”. There’s more than one reason for the bottleneck, and all those must be solved before the industry is anywhere close to supply-demand balance.

The short answer is “yes”. There’s more than one reason for the bottleneck, and all those must be solved before the industry is anywhere close to supply-demand balance.

Sarac cites Yardi Matrix as the source of those completion figures, and quotes a Yardi executive as suggesting that the decline “is part of a larger trend of developers gearing up for the next cycle.” There’s not much to support that, though. Construction contractors might put cash away for the next cycle, but they don’t turn down work. Plenty of time to rest during the next recession.

Considering how long this building boom has been going on, though, maybe the crews deserve a little break.

In a separate report, Yardi also posits that a major contributor to the slowdown is a spate of state-level rent control laws.

“After a period of below-par growth in housing stock, the U.S. needs more units built, but rent control moves the needle in the opposite direction,” according to an October 2019 paper.

It’s only three states, but two of them are New York and California — plus Oregon if it matters to you — and there are similar bills under consideration in other statehouses.

Even so, it’s rather simplistic to say that these laws are causing the slowdown all by themselves. There are, after all, reasons why they were proposed, passed and signed. Many people in these — and other — locations are rent-burdened. That is, they spend more than 30% of their monthly pay on rent. (That’s up from 25% a generation ago if memory serves.) That 30% figure is just a rule of thumb of how much you ought to pay, at maximum, for four walls and a roof. It’s pretty meaningless because rent could be well above 30% of pay for the poorest renters yet well below 10% for the wealthiest. It’s those people toward the bottom of the socioeconomic scale that rent control laws seek to protect.

So rent control doesn’t cause developers to stop building — it just causes them to stop building Class B, C and D projects. Just as there are limits to what poorer people can spend, though, there are limits to how many rich people are available to move in before the local Class A submarket is overbuilt. We talked a little about that here.

What’s Really Going on

The construction delays do come back to labor economics, but not necessarily a labor shortage.

“We aren’t facing labor shortages, but rather cost increases that are needed to ensure there aren’t any shortages,” Summit Contracting Group President Marc Padgett told National Real Estate Investor. “We have not seen an issue with the quantity of labor, but rather the cost of having it.”

A recent Forbes article reveals that, while average wages are currently rising 2.9% per year, those for residential construction workers are rising 5.0%.

The NREI article goes on to note that the typical delay on a two-year project is five months.

“Every week of construction delays results in a week of lost income, and another week during which the developer must pay the rising cost of the project’s often floating-rate construction loan,” Bendix Anderson reports.

Also, let’s remember that the two-year project plan is just an anecdotal historical average. As projects get bigger — and yes, they are — they’ll take longer to complete. A five-month construction delay on a three-year project might be more forgivable.

Reframing the Questions About Construction Delays

There will always be a preference for living in posh environs, and there will always be a preference for building big, new, shiny towers for those with the wherewithal.

So there’s no real crisis here. If your money is in limbo for a few months longer than you naively expected to have it tied up, that’s a good problem to have. After all, the same effects that are causing those construction delays on your financial return are also driving an insufficiency of supply to the market, which tends to hike up rents once the units are delivered.

So there’s no real crisis here. If your money is in limbo for a few months longer than you naively expected to have it tied up, that’s a good problem to have. After all, the same effects that are causing those construction delays on your financial return are also driving an insufficiency of supply to the market, which tends to hike up rents once the units are delivered.

The issue is at the bottom end of the scale. Everyone agrees that there’s a shortage of housing stock for lower-income renters, but industry and government seem to be talking past each other to solve this problem.

Rent control is at best an inelegant answer because, as it keeps the housing cost down for the tenant, it disincentives developers from building more units for those priced out of the market. As the Class B, C and D stock is aging past its knockdown date, it’s time for anyone serious about solving this problem to realize both price and quantity must be taken into consideration.

Are there ways to build units for less? Of course, there are. Modular construction and smaller floor space per unit come to mind. But this means governments must pass — along with or in place of rent control provisions — new building codes that would permit these. And if that doesn’t get the cost down far enough, governments are positioned to provide tax incentives and access to municipal services to serve as an in-kind partner in projects that further their objectives. A study commissioned by the National Association of Home Builders and the National Multifamily Housing Council calculates that almost one-third of the cost of an apartment building is driven by regulation, so there’s a lot of slack right there.

But even having government as a fully engaged government partner might not be enough.

We recently came across a University of Maryland study that renters could be classified as a natural resource (“prey,” the authors call them). And, just as any natural resource can be depleted, so can the renters. Is an economic model in which an entire class of people pays more than 30% of their income in rent sustainable? Or, at some point, will investors concede that a 3.75% cap rate is just about as good as a 3.76% cap rate?