The conventional wisdom is that when the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, cuts its target interest rate, mortgage applications go up. When it raises them, mortgage applications go down.

This makes intuitive sense. Like we all learned on the first day of Economics class, the demand for anything goes up when the price of it goes down, and interest is just the price we pay for money.

But we at Sharestates did a little homework and found that it’s more complicated than that. The fed funds rate is not just a dial to turn up or down the amount of money American households spend on home buying. So if you’re expecting a flood of new demand just because the Fed changed direction recently, you might be underwhelmed by the response.

“Previously, on ‘Squawk Box’ …”

The Fed — specifically the decision-making group of system governors and regional presidents known as the Federal Open Market Committee — decided at the end of July to lower the fed funds rate by 0.25%. What makes that boring little nugget of monetary policy newsworthy is that this followed nine straight rate increases over three years.

The FOMC usually raises — and rarely lowers — interest rates during economic expansions. A slow rise in these rates has the effect of limiting how much money companies and households can borrow. This, in turn, keeps companies and households from spending money they don’t have. That, in turn, keeps a lid on inflation because the fewer dollars that are in circulation, the more each dollar is worth.

But what if the opposite is happening in the economy? What if there’s panic on Wall Street, companies are going bankrupt, millions are losing their jobs and unsold inventory is just sitting on loading docks? Then the FOMC would tend to lower rates so that the money companies and households still have is worth more and, as they spend it, the economy is stimulated and eventually recovers.

That’s exactly what the central bank did in the autumn of 2007 when it got its first hint that something was wrong with the economy, i.e., when sketchy mortgages started to lapse into default. The FOMC announced one rate cut after another until mid-2009 when there was nothing left to cut. The monetary authority took the unprecedented step — unprecedented by Washington, at least, although it’s been done elsewhere — of lowering the fed funds target rate to a range below 0.25%. That is, the rate was essentially zero. It stayed there for around seven years until the FOMC took the hesitant step of raising the target range’s upward limit to 0.5%.

So why now?

The central bankers inched that limit up, a quarter percent at a time until it reached 2.5% early this year. That was a testament to both the strength of this economic cycle and its unprecedented length. We are in the midst — let’s hope it’s the middle and not the end, but who knows? — of the first decade-long economic expansion ever. But it’s still going strong despite its age.

The Fed has two jobs: keep unemployment low and keep inflation low. It’s been doing the first part perhaps too well. The unemployment rate is below what economists call the “natural” rate — that is, the proportion of workers you’d expect to be between jobs even under the best conditions. You could say the U.S. is in a state of labor shortage. Inflation is holding to a narrow band around 2% per year; any less and it would cause a disincentive to invest in anything because you might not be able to get back more money than you paid in.

So why, if everything is going so well, do we need a lower fed funds rate? There are a couple of ways of answering that, but they both come back to the same root cause: politics.

President Donald Trump has publicly scolded Fed Chairman Jay Powell for not making this move earlier, but his reasons are open to interpretation. We’ve heard a lot of theories, from electioneering under the banner of “Dow 30,000” to the positive effects lower rates would have on Trump Organization cash flows. Or it could just be that Mr. Trump believes that, at the present moment, lower interest rates are what’s best for the U.S. economy. Considering the man holds a bachelor’s degree in economics from Wharton, he must know that rate cuts aren’t always indicated, so maybe there’s another, more likely reason.

That reason would have to do with the trade war with China. Lower fed funds rates mean more dollars in the economy, and more dollars means that each dollar loses a little value and thus leads to inflation. A less valuable dollar makes U.S. goods more affordable as exports to other countries.

This trade war was one of the reasons the FOMC cited for making their move in July, suggesting it was a threat to the economy’s continued growth. To be fair, it’s not the only one — the messy divorce between the United Kingdom and the European Union has recession written all over it — but the tensions with China are impossible to ignore.

So you can say that Powell & Co. flat-out caved to pressure from the Oval Office, or you can say that it reacted to an economic reality caused by the administration’s trade policy — a campaign issue that earned Mr. Trump just enough Rust Belt votes to put him over the top in 2016 and which he needs again in 2020 — with a prudent macroeconomic fix. But either way, we have to concede that the root cause of the rate cut was indeed politics.

Still, that doesn’t mean it’s a bad idea. During the expansion of the 1990s — the dot-com boom — the Fed zigzagged three times, cutting the target rate before resuming incremental increases. A lot of people made a lot of money in those years, and the recession that followed was fairly shallow and short-lived. If the Fed is zigging and zagging again, then everything is pretty much as it should be.

If the central bank continues hacking away at the fed funds rate indiscriminately, though, that might make equity investors happy while the good times last but it would call into question the independence of the Fed. All FOMC members are political appointees, and now and then an ideologue or party apparatchik has been nominated and confirmed in the role. But they’ve mostly been tweedy, academic types less comfortable with playing to their bases than with playing with databases. If today’s Fed governors continue to lower rates from here, they might be seen — correctly or not — as having given up the independence from presidential politics that their staggered, 14-year terms provide. Should that happen, then America’s monetary policy could be determined solely by one person whose incentive is to make sure a recession doesn’t happen until after an election, rather than that it comes when it may but do as little damage as possible.

What does this mean for mortgages? Not as much as many think

But we are where we are, and the media is full of commentary about how great this move is for mortgages and, presumably, builders. But we’re not so sure.

Much of this stems from the Mortgage Bankers Association August 7 report that says mortgage application volume rose 5.3% in the week immediately following the Fed action. And we’re not saying that’s not good news. It’s just not overwhelmingly great news either, for several reasons.

The first of those reasons is, it’s only one week. Buying a primary residence is the biggest decision most heads of households make, they tend to be very careful about it and there’s bound to be a flash-to-bang lag. And sure, home buying tends to slow down in August, but not dramatically, not in the first week. According to the Census Bureau, August new home sales actually exceeded those of July in five of the past 18 years.

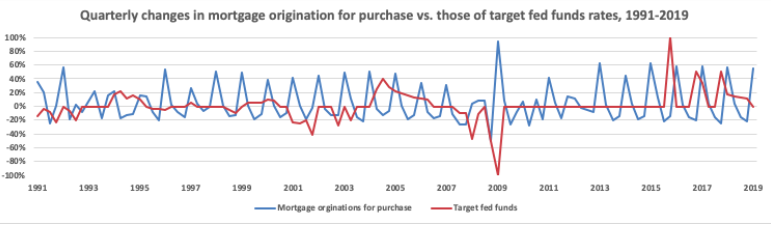

But while we’re on the topic of seasonality, what we at Sharestates were surprised to learn is that interest rate changes have much less to do with mortgage applications than the annual ritual of summer house-hunting. But we pulled some data together and that’s what it tells us:

Target fed fund rates are precise percentages prior to 2009 and subsequently the upper limit of a range. Sources: Mortgage Bankers Association, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Careful observers will notice that this chart doesn’t present actual fed funds rates or mortgage originations, but rather the quarter-over-quarter changes in these metrics. They’ll also notice that, with the exception of 2009, when the fed fund rate plunged to near-zero, its quarter-over-quarter change hasn’t provided a significant, observable stimulus to quarter-over-quarter changes in home-buyers’ mortgage apps. And that spike probably had more to do with home prices collapsing after the financial crisis rather than interest rates cratering. Since 2013 — and from 1997 through 2007 — mortgage apps simply went up by a predictable margin every summer and went down by a predictable margin every winter.

Let’s go there for a moment. Those careful observers will also notice that the data only include mortgages taken out to actually buy homes, not to refinance. It’s telling that the MBA’s data saw re-fis rise more than double home-buying mortgage app volumes in that first week of August. Also, let’s remember that the rate cut was rumored for some time, and it’s to be expected that home buyers might have been sitting on the sidelines waiting for the Fed to take action. That the MBA had reported three straight weeks of mortgage app declines in July 2019 — again, during peak home-buying season — supports this interpretation.

One more point to make about why lenders and builders ought not to rely on the Fed for market support: There’s a huge disconnect between the fed funds target rate and what home buyers get charged for their 30-year fixed.

The fed funds rate is what the largest banks charge each other for overnight deposits. It’s a fraction of the prime rate, which is the best rate banks will lend to anyone who isn’t a bank. Mortgages, even though they’re usually the lowest rates individuals will ever see, will still be higher than that, and changes won’t ever be one-to-one proportional. When the fed fund target dropped 0.25%, the conforming mortgage rate dipped only 0.07%. So the incentive for homebuyers to wait on the fed is pretty minimal, especially considering that re-fi is an option, and living in a 700-square-foot condo with three kids is not.

Also, let’s be clear what the MBA is counting in terms of volume: It’s how many billions of dollars worth of mortgages are approved, not how many units are sold. Our analysis for this post didn’t go so far as to determine how changes in fed funds correlate with changes in the number of mortgages as opposed to their aggregate value, but that might be a study for another day.

It’s clear though that if you’re looking for an economic indicator to let you know whether you should be building more multifamily buildings or how many units you should be dividing them into, fed funds really won’t give you those answers.

If you’re looking for good news, though, we’ll leave you with two hopeful notes. First, real wages — hourly pay minus inflation — have been growing since 2015 and seems to be picking up steam. Second, the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment index has been trending up — not shooting up, but trending up — and it’s in a healthy place. That is, consumers are about as happy now as they were in the mid-1980s, or during Ronald Reagan’s second term or when Nokia began selling the first mass-market cell phone in early 1997.

Also in early 1997: The fed funds target was raised a quarter percent to 5.5%, compared to today’s 2.00-2.25% range. Just sayin’.